380th Bomb Group Association

NEWSLETTER #27 -- June 2006

|

380th Bomb Group Association NEWSLETTER #27 -- June 2006 |

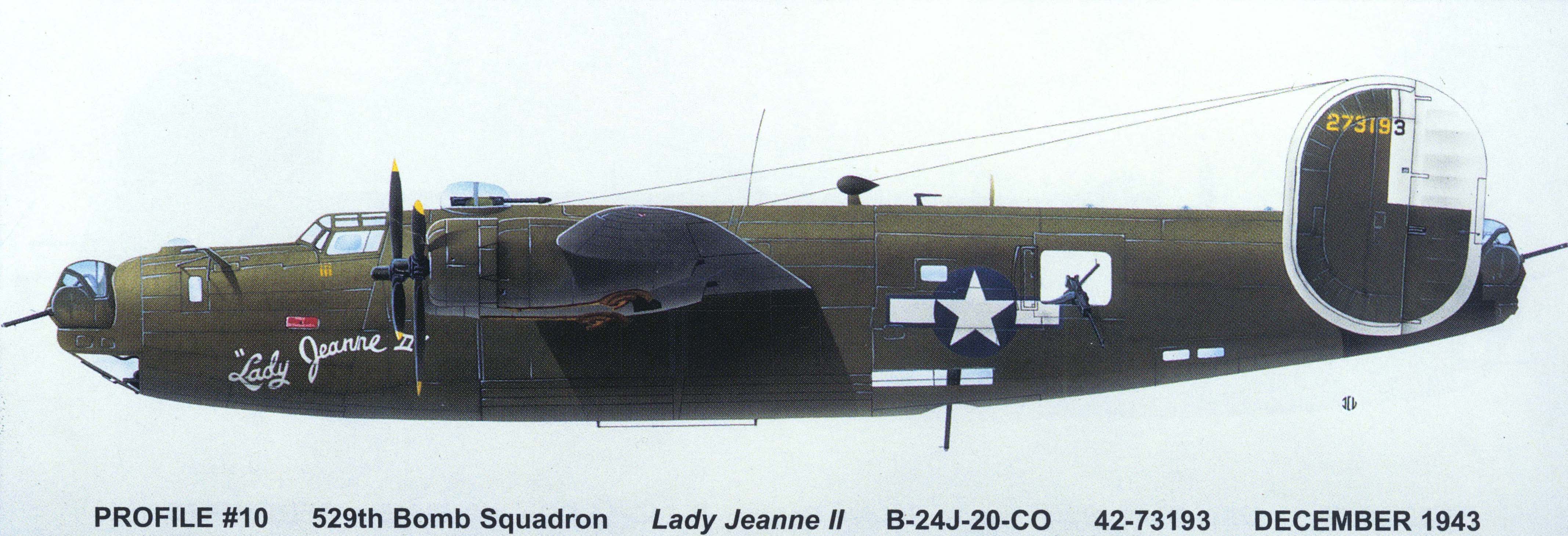

LAST FLIGHT OF THE "LADY JEANNE II"

As told to Lynn Rogers by her father,

Lt. Col. Clifton R. Toepperwein

(submitted by Bill Bever)

At the end of December 1943 my crew was sent to Dobadura as part of a push to get the Japanese out of New Guinea. Our mission was to bomb targets of opportunity to confound the Japanese build up of extra planes in that area. We were to provide extra effort and air power.

The Liberator B-24 that we were assigned to was the Lady Jeanne II which had been Capt. Soderberg's plane. His crew, except for George Platt, had each completed his missions. George was assigned as navigator, in place of Chaussee, our usual navigator, to fly with our crew in the Lady Jean for this mission to complete his missions too. This was to be his last mission before heading home.

We were briefed early in the morning and then assigned to our planes shortly thereafter. We took off from Dobadura about 4:00 AM assigned to the position on the left wing of the lead plane. We were to go up and bomb the airfield at Madang-Alexishafen to make it inactive. The formation was mostly made up of newly put-together crews (except for our crew) to train them for formation flying. Our crew was a fill-in crew to make up the sixth plane in the formation.

George Platt replaced the navigator on our crew. My co-pilot, Conway, was flying the plane on the left wing of the lead aircraft. I told Gordon, my bombardier, that Conway and I would be sure to keep his altitude and corrections if we could. He was making his own run and we were following his instructions.

As we flew over the Japanese air base at Madang-Alexishafen, we turned on the cameras and dropped our bombs. Simultaneously, the whole plane shuddered and the inboard right engine blew apart. The plane had been hit by flak. We didn't know all the damage right at that time, but the right engine had been hit and exploded, controls were severed on the right side of the plane, the bubble at Conway's right blew away, a round had gone right up between Conway's back and the metal bulkhead and taken away part of Conway's seat, and there was a gaping two to three foot hole above and straight across from Platt in the right fuselage. I shouted to Conway who had been flying the plane that I had the controls now. He released his controls, grabbed his rosary and began to recite his Hail Marys! We had to shout over the noise of the wind and the engines as we battled to keep the plane flying, and hopefully return to base.

We had dropped our bombs as the formation dropped theirs. They started a right turn to head back to the base, but we flew straight ahead of assess our situation. In seconds we had to decide the best thing to do for our crew's survival. Was the plane capable of staying in the air? We knew if we turned toward the sea to crash land, the Japanese would probably capture us. If we turned left toward the jungle, maybe we could survive there and avoid Japanese capture. We lost contact with our group, which returned to base, but we had contact with a fighter group that congratulated us for blowing up the anti-aircraft gun that had been one of our targets. (Cameras later confirmed the hit.) The fighter group offered to escort us ahead for a short distance, but then they had to return to base. I think that they might have mentioned that there were airfields recently recaptured from the Japanese beyond the mountains where we could land if we could stay airborne long enough to reach them ... I decided to have the crew stay with the plane and find a place to land.

Our severely damaged plane would easily turn right toward the ocean. The extra power from the two functional port engines made us have to work hard even to keep the plane flying straight ahead, but we wanted to turn left over the jungle because we figured our survival chances were better there. I wanted to cut back the power on the outboard engines that I had less control over. If I did, though, I probably wouldn't be able to regain lost airspeed and altitude if I needed it, and I was sure I would. So I lowered the left wing and tried to give it full left rudder. I needed my co-pilot's help to depress the rudder pedal. Conway had finished his Hail Marys by this time. Together we had the strength to push the sluggish rudder and turn the plane left toward the mountain.

I asked Platt, as navigator, if he knew of any field close by and back toward our base where we could land. When we got hit, we were flying at about 10,000 feet. Dropping the weapons and being hit increased our altitude. Platt, being the navigator, was more familiar with the terrain, mountain elevations and base locations than any other crew member. We weren't sure of the exact elevation of the mountains, but we thought that we were probably flying below the highest peaks. (Actually, we were higher than the pressure altitude indicated that we were). Our thought was to fly through a pass if we could find one. The fighter group that we were in contact with had also given us the idea that we might find a friendly base on the other side of the mountains.

Now we tried to find a base so we could land. I left it to my navigator to navigate. I depended on the navigator on any mission to get us back on the base. Thank goodness Platt had special knowledge of the area. I knew he was everyone's favorite navigator and gave us the best chance of finding a landing site.

The rest of the crew looked for airfields while Conway and I tried to keep the plane in the air. We had three engines at 70% power. The two engines on the left were working, but only one on the right wing was. To keep the plane headed straight ahead I had to lower the left wing slightly. I couldn't cut the power to the engines on the left to equalize the engine power from both wings, because the air speed would drop and the plane would go down faster. Any air speed that we lost, we wouldn't be able to regain. Conway and I had our hands full keeping the plane on course and keeping our altitude.

We were desperately hoping there was a base to land. We tried to radio a base, but couldn't raise one. We didn't know the frequency. We finally happened upon an airfield. We had to circle in. With the speed we were flying there was only one chance to land. There was construction equipment all over the runway. The tower tried to signal the grader operators to clear the runway, but the grader stayed on the runway anyway. The trucks looked like our equipment so I was mostly sure that it was our airfield, but we still weren't 100% sure that it was not held by the Japanese.

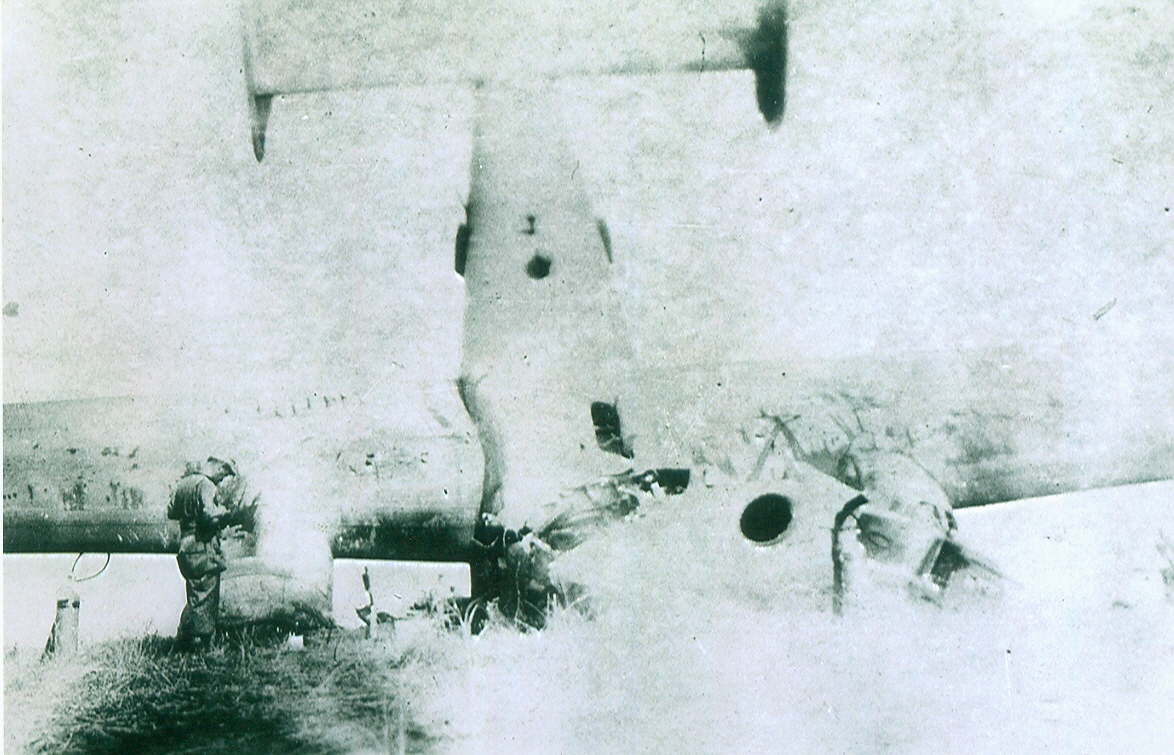

The area to the right of the runway looked like the next best alternate landing site. It was a field covered in three-foot-high kunai grass. I told the gunners that I'd decided to land in the grass. I needed them to get to the back of the plane so their weight would help keep the nose up. We started letting down at about 170 mph. I lowered the landing gear and began to cut power to get our speed down and to prevent a fire upon crashing. We landed at the end of the runway, crossed it and went into the open field. We hit a drainage ditch, which was hidden by the grass. That put the nose into the ground. The men who had been thrown forward got back again. As we hurtled ahead, we hit a second ditch and the plane nosed in again. Then the tail went up into the air and the nose bent around to the left.

My rudder pedals were pushed up under my seat with my feet on them. The instrument console, usually a few feet away within arm's reach, was now inches from my chest. I was pinned in. I couldn't move forward and couldn't move my legs to get out. I thought that the plane might catch fire. The windshield had flopped onto Conway's head and cut him. The ground equipment personnel who originally came to the plane, typically, were more interested in getting souvenirs from the plane than getting anyone out since they were not familiar with aircraft. The MPs there were interested in collecting up our 45s. (They had rifles, but wanted to keep our side arms if they could.) Their priority was to collect up the crew's 45s. I told them that I was going to keep mine until I was out of the plane. If it caught fire, I wasn't going to burn alive.

The gunners got out. Crew members who were injured were Platt, Kopel, Conway, Gordon, Bieber and me. Gordon, though scratched up and bruised, and Bieber, who had his eyes, chest and legs hurt in the crash, also got out. Gordon shouted to the ground crew (sightseers and souvenir seekers) to get their cigarettes out. He didn't want any extra chances for the plane to explode. He helped get the ground crew organized to get the rest of us out of the plane. We were still afraid then that it would explode or catch fire.

Platt reached into my medical kit and got out morphine. He took some for the pain in his legs that had been crushed by the gun turret that had broken off in the landing. He shared the rest with me and Conway. Our rescuers took Kopel and Platt out of the plane and then helped Conway. Kopel and Platt being more severely injured were taken to the hospital with others who had been shot up in a B-25 that had just crashed on the runway. That's when I lost contact with Platt. He was on Soderberg's crew so I wasn't notified of his condition. Kopel was evacuated to Port Moresby the next day. Conway was taken to get stitches for his head wound. He later told me that a dentist sewed his wound together. He then came back to the plane to see about me. They were still trying to get me extracted from the nose. After about two to two and a half hours from the time the plane crashed, they finally got a piece of construction equipment and pulled the nose away from me.

Medics at the crash tended to my cut calf that had been sliced between my seat and the rudder pedal. The pressure between the console and the seat kept me from bleeding too much, though. They bound my calf tightly with bandages to hold the cut pieces together. I couldn't put my foot down and had to walk on the ball of my foot.

MP's then took my 45. A corporal assured me that my crew and I could get our weapons back at MP headquarters when we left Gusap. They collected everyone's 45s…those of the B-25 crew too. Since Platt was the most injured of our men, I was led to believe he was one of those evacuated with the B-25 crew the next day.

That's about the time Conway arrived back, and we shared some beers. It happened this way. People checking the airplane found two beers which had been hidden some place in the nose compartment with the ground crew equipment. The ground crew back at the base in Australia may have sent the beer up with us expecting to enjoy some cold brews when we got back. Beer was forbidden in New Guinea. The man wanted to know how to dispose of it. I took one and handed the other to Conway, and we disposed of the beer.

Conway and I were hungry. It was about 1:00 PM now and we hadn't eaten since morning. One of the MPs drove Conway and me up to the mess tent. A mess sergeant coming out of the tent told us the mess tent was closed until 6:00 that evening. Then he got in his jeep and left us standing there. Our MP ride had left too. Conway and I hobbled back a half mile toward the hospital tents. The morphine and beer we'd taken earlier did their job. His head and my leg didn't even ache.

That afternoon we listened to the short bursts of gunfire exchanged between

our troops and the Japanese some of whom were still hanging around firing at

targets of opportunity. That night all hell broke loose. Guns were firing all

over the place. A corporal

who

was our protection from the enemy came into our tent, flashlight shaking in his

hand, stuttering, "I…I…I…I'll protect you." We thought the Japanese were trying

to recapture the base, but were told, after 15 minutes, that seemed like at

least an hour, that it was only our fellows celebrating New Year's. The next

morning we heard that three fellows had been killed by falling ammunition.

who

was our protection from the enemy came into our tent, flashlight shaking in his

hand, stuttering, "I…I…I…I'll protect you." We thought the Japanese were trying

to recapture the base, but were told, after 15 minutes, that seemed like at

least an hour, that it was only our fellows celebrating New Year's. The next

morning we heard that three fellows had been killed by falling ammunition.

I've thought about how I felt as all this was happening. I was too busy trying to figure out what was best for my plane and crew and taking actions to keep flying to be aware of feeling anything. We approached the targets. Just as we dropped our bombs, the engine on the right wing exploded and controls on the right side of the plane were severed. We started to lose altitude and dropped out of formation. We had just seconds then to begin making decisions and taking actions to keep our plane in the air, turn it, fly it and get across the mountains. We didn't waste any time finding a safe place to land at the Gusap strip. Since there were men and trucks all over the runway, I opted to land in the field. Without brakes, flaps or the use of the nose wheel, we brought our plane down for a landing even though we were traveling at 140-180 miles per hour. Then, once we were on the ground, we had to get people out of the plane and worry about whether it was going to explode or not.

I was too busy doing what had to be done to think much about how I was feeling at the time. I relied on my men to do their jobs, and they did. I was sort of a fatalist. If I was going to die, it would happen. If it was fate for me to live, I would. I do know that facing the flak guns on the next mission that I flew was one of the hardest things I ever did in my life. I'm grateful the Lord was flying with me.

Lt. Colonial Clifton R. Toepperwein was assigned to the 5

th AAF, 380th Bomb Group, 529th Squadron, when this aircraft accident took place.