380th Bomb Group Association

NEWSLETTER #30 -- April 2007

|

380th Bomb Group Association NEWSLETTER #30 -- April 2007 |

DREAM TIME - A WAR STORY

INSTALLMENT #3

by Robert W. Caputo

This is a story of one person's experience in World War II and the title grows out of the time served on the Continent of Australia (the term "Dream Time" is borrowed from the Australian Aborigine use of the term to describe the distant past of mankind). The writing was done because of the urgings of one family member and was completed in 1995. No claim is made that the story is one of a kind or especially unique, no more than each of us is some different from the other. Reproduced here by permission of the author.

Because of the length of the manuscript, we will tell Roger's story in various installments, in succeeding issues of THE FLYING CIRCUS Quarterly, as page space permits.

Roger Caputo was an NCO who was assigned to Group Headquarters, Administrative Section, in Intelligence.

"Daddy, what did 'ya do in the War?" Answer, "In El Paso your Mother and I became engaged!" The El Paso campaign was all victory for me!

During the fall term of 1941 and the spring term of 1942, at the small liberal-arts college in Alton, Illinois, Virginia and I started dating on weekends, the only time I had free. She was a year ahead of me in school even though I was 13 months senior to her. We had attended Woodriver High School at the same time, but I was a senior transfer student and our paths never crossed. I had lost time with my higher education schedule because I had taken time out to learn to fly after trashing the scholarship to an Illinois State Teachers College. I wanted to fly, not be a teacher. So much for the whims of youth! It was in the fall of 1941 when I observed Virginia, sitting alone between classes in the tiny Student Union working over her books, when I decided to approach her and introduce myself. I displayed no lack of confidence. I continue to puzzle over how people are sometimes drawn together and their lives are forever changed. So it was with Virginia and me. While dating we had some wonderful times together during the 1941/42 school year. Since I was working and had a car plus some extra cash, we could do things the normal college students couldn't. We went to a lot of dinner dance places just as a couple and danced and danced to the big band sounds. She was a dream to dance with; I was only average. Given that school year alone, my hindsight is we imprinted each other. It was a romance in the finest tradition. Wisdom, as a young man, was not my long suit and when the spring semester of 1942 ended and the summer came on, somehow we drifted apart and were not seeing each other … neglect on my part was the cause.

War sometimes involves romance as well as battle and as I sat stupefied in El Paso, I resolved, after a lapse of 6 months, to phone Virginia and reestablish contact. It was much more than reestablishing contact. Brash as usual, I asked her over the phone if she would marry me if I ever returned home. She said, "Yes!" Whoopee, somebody will have me, and life for me took on real meaning! To solidify the engagement, for that was all it could be for the time being, I invited her to come to El Paso over her Christmas vacation from school and I sent her money to come by train first-class with a roomette all to herself. Nothing was too good for my betrothed!

At the first opportunity, I hurried to town and shopped for a diamond engagement ring (it was the best I could pay for, but it was a visible symbol of the engagement). The next problem was arranging for a place for Virginia to stay while visiting in El Paso. At this point, I took my problem to my Captain who had considerable influence with the El Paso Hilton Hotel management. The Captain was quick to go to bat for me and said, "Sure, I'll get you a room." I replied, "Sir, you don't understand, I need two rooms." The Captain raised his eyebrow at my amended request, but he did get the rooms and everything was set.

On the appointed day, Virginia arrived, but in reviewing the details of the visit with her, neither can remember whether I met the train and a whole bunch of other details have been lost from our combined memories. One detail of the night is retained by us both: we had one big night out on the town! The Mexican city of Juarez lay just across the Rio Grande River from El Paso and a pedestrian footbridge made for an easy crossing. We strolled over to Juarez, did some sightseeing, and had dinner that evening in the best Mexican restaurant available. After dinner, we walked back to the hotel. I stayed in my room that night and Virginia in hers. Given the social behavior of today, the story may sound corny, but that's how it was done in those days by a couple of conservative Midwesterners and we are proud of it. The details of her departure are also lost to our memories, but she did get home in the same condition as she arrived with the exception she now wore an engagement ring that said to all predators, "stay away, she belongs to someone."

The Military in its great wisdom decreed that our Group should not complete its final phase of training in El Paso, but should be moved to Denver; no reason given, just do it. The aircrews flew their airplanes to Denver, an easy trip. The Ground Echelon went by train in early February of 1943. It was winter and cold in Denver and the heating system on the train was frozen, which didn't add anything to the comfort of the trip. If there was nothing to do in El Paso, there was less to do in Denver. I requested and was granted an extra long weekend pass for a visit home. There were two days at home and two days on the train. It was worth it. I got to spend some time with Virginia and my folks. As it turned out, the visit would be last time I'd get to see them until September 1945, or 2 ½ years later, a long, long time!

The aircrews continued with their flight training with emphasis on long-range navigation and some of the stories generated out of this were unbelievable. Navigators' ability to navigate apparently had gone undeveloped as they had relied, up to this point, on the civilian low frequency radio beacons in use by the airlines. Those guys weren't ready for those 2,000 mile, over-water legs they'd have to fly to get to Australia; of course, they didn't know that's what they would ultimately have to do. So our stay at Denver was continued for an extra month to 6 weeks to whip the navigators into shape. While we were at Denver's Lowry Field, we were inspected by lots of top brass checking on the Group's fitness. The heat was on. Later, we found out that Roosevelt had promised Churchill to send a group of heavy bombers to Northern Australia because the Japanese had taken over all of the Dutch East Indies, placing them only 500 miles from Darwin, Australia's northernmost town. Darwin hardly merited being rated as a town. It was but a minor seaport for shipment of beef to the Empire. The story is told, that during one or more of those inspections, in addition to all the unfitness detected, an honor guard really blew it with their inability to do drills (remember, they hadn't had any infantry training). So the Inspecting General lost his cool and remarked, "This is a Circus," and the name stuck and we adopted the official name of "The Flying Circus, King of the Heavies," and our Group logo became a lion sitting atop the globe. There were four squadrons which made up the Group and each adopted a logo of its choice. Each Squadron had the same organization as the Group Headquarters where I was posted, i.e., the S-1, S-2, S-3, and the S-4. There was a lot of needless duplication, but then that's the Military. The idea was that each Squadron was able to go off an operate on its own if need be, really not a bad idea, but they were never called upon to do so.

The third week of April we packed our gear and fell out in formation to board a troop train for the port of embarkation (POE). It was a bitter cold day with snow on the ground and it seemed we stood there for hours shivering in the cold while the people counters did their thing and assigned us to our sleeper cars. It was to be an overnight train ride to San Francisco, although we weren't told just where we were going … security, you know, "the enemy is listening" was the by-word. The cars were standard Pullman rail coaches with upper and lower bunks which were designed for one person in each bunk, but we were lodged two to the bunk. There was barely enough room for two in the bunk and then only if each party lay flat on his back with his arms folded across the chest. Ralph Finch and I were upper bunk buddies as we had become friends and shared some of the same cultural values.

Sometime during the night I woke up feeling sick and determined that I had a fever. The on-duty doctor, a Captain Glass, told me I had a fever of 105, and gave Finch orders to get out of the bunk; I don't know where he spent the balance of the night, but I had the bunk to myself the rest of the trip (which I don't remember, since I slept all the way to San Francisco).

When the train pulled into Camp Stoneman, the medics took me off the train on a stretcher, and an ambulance took me to the Base hospital, where I was put into quarantine. In due time a hospital staff doctor checked me over and the diagnosis was scarlet fever! In August of 1942 I was afraid I wouldn't pass the physical, now I had a new worry: would all my buddies get on the boat and leave me behind to heaven knows what? "How soon can I get out of here?" I asked the doctor. He just shook his head! Next day the medics brought in Ralph Finch, my bunk buddy on the train. He had come down with the scarlet fever also. Ralph was also very upset about the prospects of missing the boat, but there was nothing we could do about the situation.

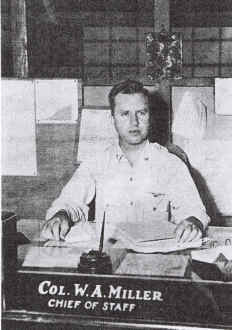

Somewhere after El Paso our S-2 officer, Captain Miller, disappeared and a new officer was assigned to run S-2. His name was Captain Joe Burkes. He too was a lawyer in civilian life and was from Seattle. The Captain was a regular fellow; he used rough language and didn't believe in red tape; as a matter of fact, he was an expert at cutting it! In about a week he came around to see us, staying at a safe distance. We appealed to him to get us out of there, we didn't want to be left behind when the boat sailed. He said he would do it, not to worry.

At midmorning on May 5, 1943, Captain Joe showed up and said, "Get your gear together, I'm taking you guys out of here now." We had been in the hospital about 10 days and were feeling better, but still pretty weak. We wondered about the propriety of breaking out of quarantine, but if Captain Joe said it was OK, who were we to argue; we were going to catch the boat and that was the main thing! Captain Joe carried our gear since we were too weak to carry it ourselves. It must have been some sight, two pale, too weak to hardly walk, enlisted men struggling up the steep gang plank with a Captain dragging their gear and bringing up the rear! It was a very democratic Army that day! We had no more than stepped on deck when the gang plank was removed and the ship was under way.

Much later I finally learned how Captain Joe was able to get us out of the Base hospital at Camp Stoneman. He was touched by our appeal and so he went to work with the surgeons in our Group and they lobbied the base hospital doctors to release us to our Group on the promise that we would be put in sick bay as soon as we boarded the ship as insurance against our infecting the entire ship's company. The base doctors were being super cautious, as they should be, while our Group surgeons were being more practical and working from experience. Immediately upon boarding, we were conducted to the ship's sick bay and locked up in quarantine. Once the ship sailed outside the 3-mile limit, it was no longer under the jurisdiction of the Continental Command and new authority took over. The next morning Captain Joe had us released from quarantine and we were free to join the rest of the troops.

The ship was the US Mt. Vernon, a 27,000 ton cruise ship converted to carry troops. The lower decks had been stripped of all the civilian trimmings and fitted out with bunks. The arrangement consisted of tubular framing from deck to overhead (that's nautical language for ceiling) with the canvas laced between the horizontal members. The vertical spacing between bunks was about 24 inches, packing the sleeping troops in as tight as packages on a shelf. When Ralph and I went below decks to claim a bunk, there were none left. The ship's crew then issued us folding cots and we were shown where to set up on deck, out in the open except for a canopy that extended from the deck house to the railing. We were not the only ones, there were several others. There we slept for the next 16 plus days at sea, just one big step from going over the edge and into the sea. If my Mother would have had the slightest notion that her sick, but recovering, son was sleeping out doors after a bout of the scarlet fever, she would have been beside herself. Actually, I believe the fresh salt air was excellent therapy. We arrived in Australia in good health!

Sleeping on deck was a bit chilly for the first few and last few days of the voyage, but a couple of those heavy Army O.D. blankets did the trick. The only problem with sleeping on deck was we had to tear down our cots each morning and re-erect them each night. The ship's crew began their morning routine at daybreak each morning and it was violent. They came down the deck with fire hoses, flushing down the surface with sea water. We had to be up, gear stacked, and out of the way, or be drowned!

The middle third of the voyage, from 15 degrees North Latitude to 20 degrees South Latitude, we encountered warm to hot ambient temperatures and the below deck parts of the ship became insufferably hot. The troops could not tolerate the conditions, so they spent all but their sleeping time on deck with nothing to do. Our cots, located on the deck, were very comfortable sleeping. With all the troops on deck, it did not take long for the card and dice games to break out. The congestion on the deck sometimes interfered with the ship's crew performing their duties. The ship's captain became frustrated and he had a few salty remarks to make about the troops' priorities to the effect he believed the gambling would continue even if the ship was sinking! I simply watched. War seemed very, very far away. Meals were served three times a day with certain groups scheduled for certain times. Eating was accomplished standing up to narrow tables, about chest high, bolted to one of the lower decks. The tables had rims around the edge to restrain any sliding mess kits from falling on the deck. I'll never forget the first meal I took. We were only a short distance out of San Francisco and still in what is known as ground swells, so the ship pitched and rolled and we didn't have our sea legs yet. The meat dish was greasy pork chops. It was too much for me and I didn't eat.

I never had an exact count of how many troops were on the Mt. Vernon, but we were not the only ones. There were about 2,000 of us in the ground echelon and we were just a very small part of the total troops on board. I'd heard rumors there were 10,000 of us, but I think someone stretched the facts a bit. There were thousands, but just how many I never knew.

At dawn on May 21, 1943, the Mt. Vernon slowly nosed its way into the harbor of Sydney, Australia.

|

|

The brass arriving at Lowry Field, Denver, 1943

|

Inspecting the books, Lowry Field, Denver, 1943

|

|

|

| Moved up to Bomber Command | Captain Joe Burkes |

More to come!

Return to Newsletter #30 Topics page

Last updated: 22 May 2014