380th Bomb Group Association

Newsletter 38 ~ Spring 2009

|

380th Bomb Group Association Newsletter 38 ~ Spring 2009 |

DREAM TIME - A WAR STORY

INSTALLMENT #8

by Roger W. Caputo

This is a story of one person's experience in World War II and the title grows out of the time served on the Continent of Australia (the term "Dream Time" is borrowed from the Australian Aborigine use of the term to describe the distant past of mankind). The writing was done because of the urgings of one family member and was completed in 1995. No claim is made that the story is one of a kind or especially unique, no more than each of us is some different from the other. Reproduced here by permission of the author.

Because of the length of the manuscript, we will tell Roger's story in various installments, in succeeding issues of THE FLYING CIRCUS Quarterly, as page space permits.

Roger Caputo was an NCO who was assigned to Group Headquarters, Administrative Section, in Intelligence.

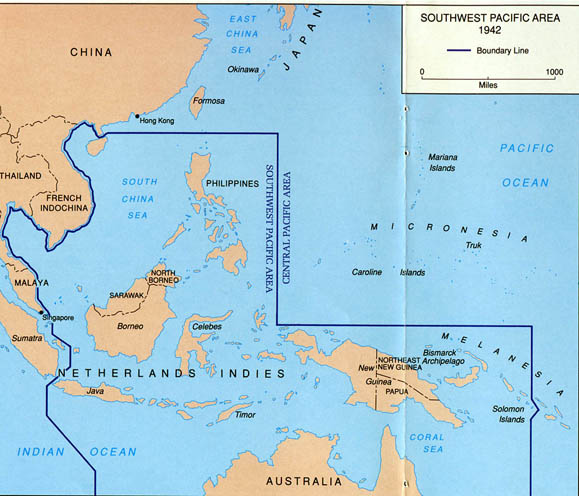

The Japanese nearly took New Guinea, and would have, had it not been for the brave Aussie foot soldiers who fought them to a standstill along the crests of the Owen Stanley Mountains that form the so-called backbone of the Island. They bought time with their lives and the Japanese never attained the crests, the high ground, and were stopped on the Northern slopes (New Guinea, a long island, generally lay East-West). The Japanese movement into New Guinea was from other islands generally to the North and from the West out of the Dutch East Indies. It was the job of the 380th to pin down and disrupt the movement from the West and we were strategically located in the Northern Territory to whack them on their Southern flank; and whack them we did!

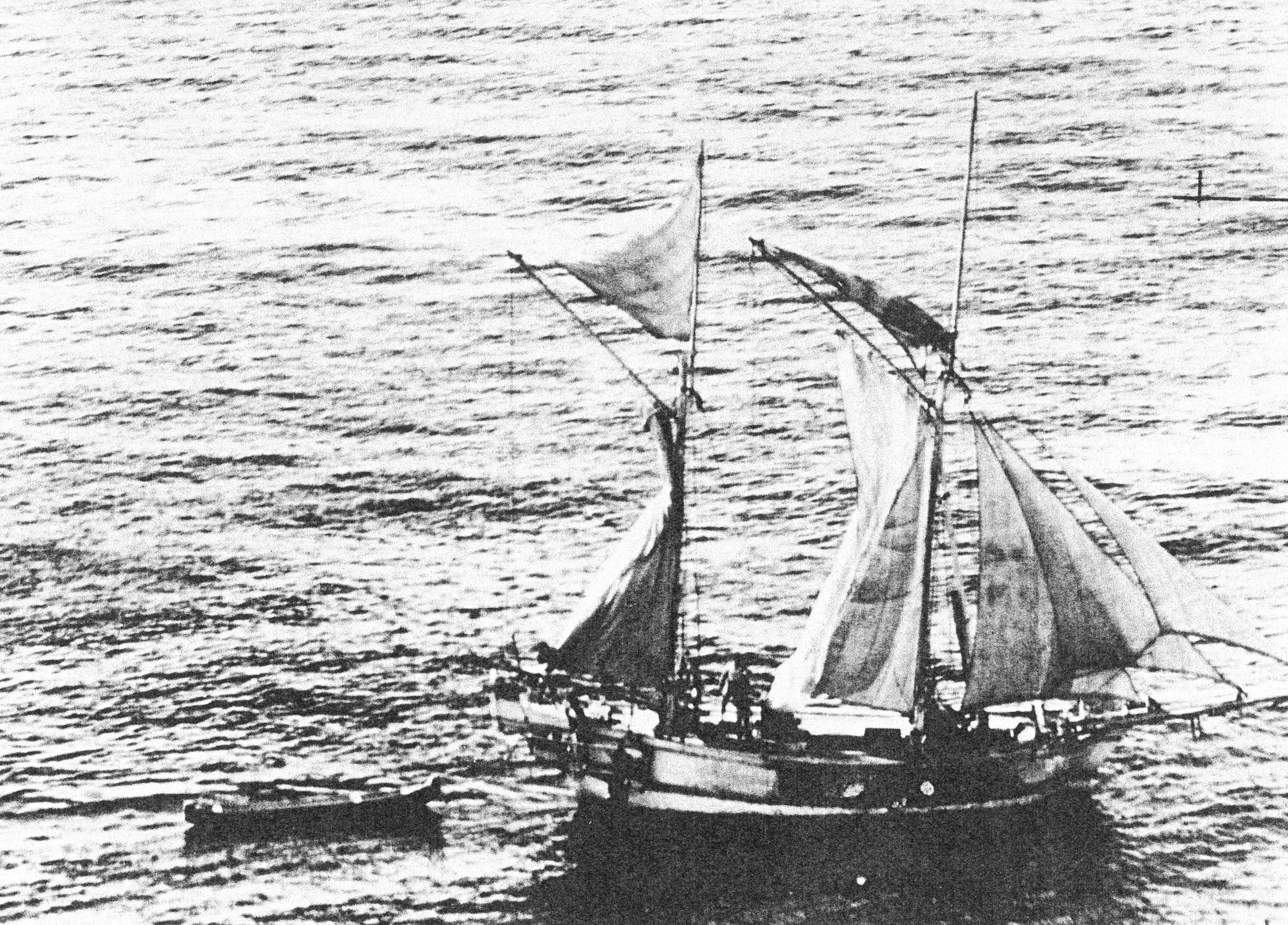

We pounded the Japanese in Western New Guinea (that was originally held by the Dutch); the Island of Ceram; the Aru and Kai Island Groups all in the Banda Sea; the Celebes; and Ambon Island. The Japanese had occupied so much territory so quickly they didn't have the shipping to service it. All these islands had a lot of inter-island commerce prior to the war by means of native-owned small sailing ships, often called luggers, with a small engine to negotiate the harbors. Unfortunately, these small sailing ships became targets as the intelligence was the Japanese were hiding behind the natives and we had to attack them because of the cargo which was in turn supporting the Japanese effort. On one raid to the Northern Celebes a huge shipyard was fire bombed where the Japanese had under construction as many as 50 of the luggers at one time. The raid made a great fire as the luggers were made of wood. The shipyard never resumed operation.

Lugger

The Celebes was a target hit over and over again because of the nickel mines and the City of Makassar, the principal port. The enemy was sensitive about this and mounted a substantial defense with fighters any time we attacked. Our most dramatic losses occurred when we attached the Celebes. One raid on Makassar produced an unexpected result: a Japanese cruiser was caught moored to the dock as the bomb run started and the bombardier had the Norden sight zeroed in on the docks, the assigned target. Suddenly, the bombardier noticed the cruiser and adjusted the sight accordingly and very neatly put a couple of bombs right on the deck. Some time later the intelligence was that particular cruiser had to return to Japan for major work in dry dock. Ships are very, very small targets and if they are moving, the evasive action they can take in the open sea almost guarantees a miss.

On the Island of Borneo, the largest, at the town of Balikpapan there was a harbor and most of all an oil refinery: the Shell Oil Co. The harbor could always be counted upon to contain numerous merchant vessels and perhaps an oil tanker or two. The round trip would be about 2,600 miles if the departure was from Darwin, 100 miles to the north of Fenton. The B-24s were designed for a maximum gross take-off weight of 56,000 pounds; for the mission to Borneo the gross would be 66,000 pounds! The fuel was 3,500 gallons in the wing and auxiliary bomb bay tanks leaving room for six 500-pound bombs. No formation flying was involved; 12 bombers were in single plane elements, spaced a few minutes apart. They took off at dusk; flew all night through multiple tropical fronts; struck the target with maximum damage; there was very little or no resistance as the raid was a total surprise and they all returned home, though one plane just made it to an Australian ocean beach with fuel exhausted and put it down easy. The airplane was repaired and flown off back to base to fight again. Those missions were 16 to 17 hours long and had no equal for distance!

Just getting there and back was no mean feat, not to mention the fact that on the first raid the shipping anchored in the harbor was skip bombed at masthead height and two were sunk as revealed by photos taken on subsequent missions. The oil refinery was set ablaze, with smoke towering in the air higher than the airplanes.

The mission to Soerabaya, Java, was the second largest mission; a round-trip of 2,100 miles. From Fenton or Darwin it would have been 2,300 miles. The purpose of the mission was more harassment than anything else; just a notice to the enemy that he was not safe anywhere. To carry out this mission, the aircrews and ground support people staged into a place called Marble Bar, a West Australian desert town. This all was done only once and anyone who had to stage out of Marble Bar agreed once was enough!

There was one mission more than any other that stayed fixed in my mind, because I actually felt that I contributed something, even though it was more by happenstance than for any other reason. A look at the Dutch East Indies will show that a chain of island, beginning with Sumatra as the first, and working eastward there is Java, then Bali, then Lombok, then Sumbawa, Sumba and the Flores, and finally Timor. This chain of islands is principally volcanic in origin. A very small one, Krakatoa [Indonesian: also known as Krakatau], was an active volcano cone and in August 1883 it literally exploded, killing 36,000 people by tidal waves, and dust was spewed into the atmosphere in such large quantities that the weather in the Northern hemisphere was so altered that there was no normal summer in 1884! The island disappeared!

The Japanese had removed some coastal defense guns from Singapore, after it was captured from the British, and relocated them on a cliff on Lombok Island overlooking the Lombok Strait between Lombok and Bali. The U.S. Navy submarines preferred to use the Strait when transiting from the Indian Ocean into the Java Sea. The currents in the Strait were very strong and the subs wanted to travel the Strait while on the surface. The presence of the coastal guns made the subs on the surface sitting ducks. The Navy sent the 380th a request to take out the guns and mission planning began. The Group Commander and our Section S-2 Officer were having an informal discussion concerning the best ordnance to drop on the target, altitude for the bombing run, and so forth. They were standing very close to me and I could not but help overhear the discussion. Everything I was hearing did not check with what I had seen on the target photos. The Japanese had dug in the guns and protected them with a log emplacement covered with soil. I knew it would take a big bomb to do much damage and these two officers were talking about 500-pound bombs and carpet patterns. I simply couldn't stand the misguided conclusions they were developing and I butted in: "Excuse me, Sirs, I couldn't help but overhear and I would like to offer that my studies of the photos indicate much larger bombs, dropped with precision from low altitudes, will be required to take those guns out." The two officers considered my recommendation for a moment and agreed my analysis was correct.

The bombers were loaded with 1,000-pound bombs and they were dropped from 10,000 feet. The target was totally obliterated! There was no evidence of any guns, logs, or anything else where the emplacements had been; only one mass of overlapping craters in the after strike photos. The Navy sent us a telegram of congratulations; they were overjoyed at the prospect of hazard-free transit of the Lombok Strait!

As I reflect back on this experience and look at all the factors that came together to create the success such as: bombardiers with expertise; two Officers willing to listen to the input of a brazen and confident T/Sgt who had been to a military photo school and whose knowledge was reinforced by the grand total of one year's training in college level engineering; the question has to be asked: "Does everything happen by accident?"

With the passing of this highpoint in my military career, I could have just as well gone home without altering the timing and conclusion of the war's end. However, I was "invited" to stay on, just in case some other unexpected crisis should arise and I might be needed!

Map source: http://www.1uptravel.com/worldmaps/history-ww2map29.html

More to come!

Return to Newsletter #38 Topics page

Last updated: 22 May 2014