380th Bomb Group Association

Newsletter 35 ~ Summer 2008

|

380th Bomb Group Association Newsletter 35 ~ Summer 2008 |

DREAM TIME - A WAR STORY

INSTALLMENT #6

by Robert W. Caputo

This is a story of one person's experience in World War II and the title grows out of the time served on the Continent of Australia (the term "Dream Time" is borrowed from the Australian Aborigine use of the term to describe the distant past of mankind). The writing was done because of the urgings of one family member and was completed in 1995. No claim is made that the story is one of a kind or especially unique, no more than each of us is some different from the other. Reproduced here by permission of the author.

Because of the length of the manuscript, we will tell Roger's story in various installments, in succeeding issues of THE FLYING CIRCUS Quarterly, as page space permits.

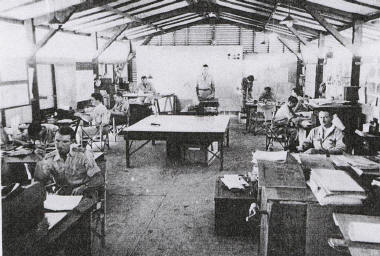

Roger Caputo was an NCO who was assigned to Group Headquarters, Administrative Section, in Intelligence.

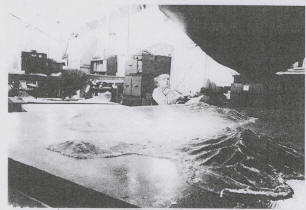

The aircrews seemed to consistently have target recognition problems while often dropping bombs wide of the target. Getting into position for a bomb run was not easy. The preferred route was always from sea to land to avoid anti-aircraft fire which was always land-based. To identify some unmarked point on the surface of the sea, at which point the aircraft was to align itself for the run, was difficult, to say the least. Colonel Miller, the Group Commander, appealed to the Aussies for suggested solutions to the problem. They claimed to have the answer: it was to build large scale, three-dimensional relief models, around which the navigators could huddle and imprint the island targets in their minds. The idea was to minimize the recognition problem. Some targets would be struck once and then never thereafter, so they had no opportunity to practice where to make the proper turn in for the bomb runs. Further, the Aussies were operating a how-to-do-it school in Brisbane for would-be target model builders. Two other enlisted men from the Squadron's S-2 and I were sent to Brisbane, on two weeks TD, to play in the sand boxes.

The duty in Brisbane was interesting, but at the same time dull, because the town was wall-to-wall soldiers. We rented space in a small second or third class hotel and we were comfortable. The local motor pool furnished us a jeep for travel from the hotel to a big warehouse containing the so-called school. A one-page, type-written report could have contained all we learned in the two weeks. The Military's strong pint was not efficiency!

There were only two features of the Brisbane experience that are of story value. A DC-3 flown by a Dutch Army pilot, a refugee from the Dutch East Indies, picked us up early in the morning along with others and we started for Brisbane. About noontime, or shortly thereafter, as we crossed from the Northern Territory into the province of Queensland, a huge dust storm lay across our flight path. The pilot decided it was a no-go situation and he turned around, located an emergency dirt airstrip, and landed in the middle of what appeared to be nowhere. Very shortly one of those Aussie lorries came bumping along and picked us up and transported us to a rail point. There stood a huge old two-story Victorian frame house with a windmill beside a narrow gauge railroad. We waited a couple of hours and in late afternoon, a small wood-burning engine, towing two small wooden-rail coaches, made a stop for water and rest. We threw our gear aboard the coaches and climbed in. The coach seats were made of wood and resembled those normally found in parks. The coach windows were the double-hung type and they had to be opened for ventilation and the black smoke from the engine rolled back over the coaches and in through the windows. We tried various window adjustments as a compromise between keeping cool and being blackened by smoke. We were enroute about 15 to 16 hours, arriving in Brisbane around 0800 hours the next morning; no sleep and soot-blackened from the smoke. At frequent intervals, during the night journey, the train would make rest stops, always beside a small building where the interior illumination was a kerosene lamp sitting on a table. Also to be found on the table was a tray of biscuits (cookies) and hot strong tea. It was a serve-yourself arrangement with a frontier-type woman usually in attendance. Also on the table was a tray with a few coins in it, indicating that a donation of a couple of shillings would be appreciated. We were generous with our contributions!

Upon arriving at the hotel in Brisbane, we stripped off our blackened clothes, took a bath, and crashed into bed. We were dead tired; the War could wait until the next day! Recognizing how the interest in tourism has grown worldwide, I can now fancy how some folks, making the same trip today, would be charmed by the experience, of course without the black smoke!

The return trip to the Northern Territory was uneventful. The Colonel was anxious for us to get to work on making target models and two targets were assigned as being most important. I only remember one, it was Ambon on the Island of Ambon, which lay just west of Dutch New Guinea and east of the Celebes Group, and we were ready to roll up our sleeves and to go work. There was one small problem; none of the materials available in Brisbane for model building were present in the Northern Territory! The Colonel expected the models and we had to improvise and we did. In the 1930s and 40s, a particleboard known as Celotex was used in home building for exterior siding (it was a failure as siding) and something very similar to it was available from the Aussie Army engineers in unlimited quantities, but it came as sheets about ½ inch thick and 4x8 feet. Using only our hands, it had to be shredded into very small pieces, so that it could be molded into various shapes needed. Pressing it together required large amounts of adhesive to bind it and there were no glue factories in the Northern Territory! There was a mess hall, and it had lots of wheat flour. Calling upon our boyhood experiences with building kites from newsprint and flour paste (they never flew well, too heavy); we made gallons and gallons of flour paste and formed the models. In the high humidity, some models took forever to dry, but they eventually did. Various colors of paints were also available from the Aussies, so we painted the entire model a dark green which simulated the jungle which covered all the islands. Contrasting colors were then used to indicate towns, roads, airfields, and the like. Ralph Finch was a commercial artist by trade (he did matchbook cover artwork) and he could do wonders with a fine-pointed brush.

At last the first model was finished and we displayed it to the Colonel. "Excellent! Excellent!" he remarked, and rushed out to bring some of his staff to see it. They mostly just stood and stared at it and made hardly any comment, good or bad. We built a second model and it received the same level of review! As I remember, the models were used once or twice by HQ operational planners, but I have no memory of any aircrews ever seeing them. War is crazy: there were the airmen, 10 to the bomber, going out on 1,000 mile missions, running the gauntlet of tropical storms, Japanese anti-aircraft fire, attacks by determined Japanese interceptors, running the risk of having to ditch a disabled bomber at sea in shark-infested waters, or worse, captured by the enemy and tortured; while we office types were safe at base playing in our sand box!

The models were finally stored away and never used thereafter. Months and months later, I came upon them and touched them with the tip of my finger and then the surprise: beetles had bored their way into the models and had a feast on the flour paste, leaving the models a fragile shell made up of the outside coating of paint! So much for the permanence of things made by mankind!

|

|

|

| Group HQ Intelligence, Fenton | Target Model, Ambon Harbor |

More to come!

Return to Newsletter #35 Topics page

Last updated: 22 May 2014